The highlands has many remote and difficult to access spots, but few capture the imagination quite like the island of St Kilda. A journey to this near-mythical outpost, 40 miles into the Atlantic, is akin to approaching the edge of the world as well as stepping back in time. What is it that captivates us about this barren and isolated outcrop of rock, barely visible from the civilization of North Uist?

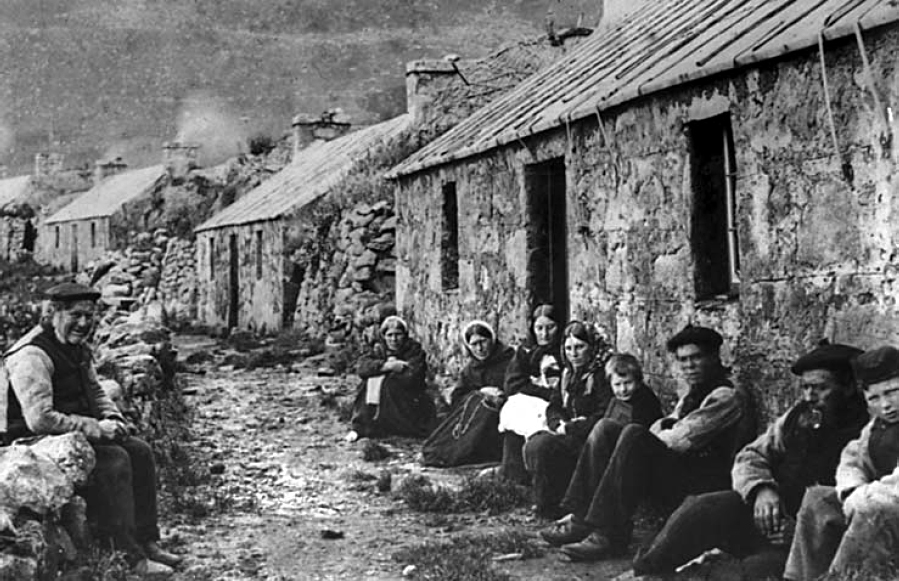

Recent excavations have unearthed evidence that shows inhabitation on the islands as far back as Neolithic times. The islands were self-sustaining, prosperous and self-governing and, until the arrival of Christianity in the 18th century, a place of largely druidic beliefs. Periodic contact with merchants and sailors led to the spread of diseases, which had a huge effect on the population, but despite the hardships of island life the death knoll for the traditional way of life came in the aftermath of the First World War.

The departure of many of the islands young men, and particularly bad harvests, led to the islanders requesting to be evacuated to the mainland. The last remaining 36 islanders were settled in Morvern in 1930. The afternoon the St Kildans arrived on the Princess Louise, the Lochaline pier was packed with people – journalists, photographers and locals. Journalist and photographers had not been allowed to record the leaving from Village Bay on St Kilda, but they arrived by motor launch during the afternoon and herded themselves onto the pier alongside the local people.

Subsequently the islands fell into the ownership of the Marquess of Bute who bequeathed them to the National Trust for Scotland, and in 1957 the area was designated a national nature reserve. This coincided with the island becoming permanently inhabited once again, by a small number of civilians employed by a defence contractor, working in the newly constructed military base. During the summer months, a small number of conservationists and work parties also live on the island. It is now a protected environment so permission is needed if any passing ships want to land, or if anyone wants to spend the night.

St Kilda is also Europe’s most important seabird colony, and one of the major seabird breeding stations in the North Atlantic. The island is one of the few sites on the planet to be to be awarded ‘mixed’ World Heritage Status, in recognition of both its natural and cultural significance.

One of the most infamous ever residents of the island, albeit against her will, was Lady Grange, the wife of the – then – Scottish Lord Advocate. After their separation she accused him of being a Jacobite sympathiser to which he responded by having her kidnapped and imprisoned on North Uist and then St Kilda, where she remained for 8 years. After a failed rescue attempt she was eventually moved to Skye where she died in 1742. The ramshackle remains of her house are still to be seen in the village meadows. The story was told in a recent bestseller by Margaret Macaulay entitled ‘The Prisoner of St Kilda’.

Another St Kilda curiosity is the legend that surrounds the ritual that young men had to perform before they were able to marry. To prove they were able to provide for a family by climbing the rocks to catch birds for food, in front of the whole community, they had to balance on their left foot over the edge of a protruding rock. Then they would have to place their right foot in front, bend down and make a fist over their feet. It is not known how many people died performing this or when it was last deemed necessary, but at any rate the rock outcrop associated with the practice is still there and every year some visiting daredevil tries to impress his other half by recreating the stunt.

A journalist stranded on the island during a harsh winter famine in 1876 devised a method of sending a distress signal to the outside world. Mail was sealed inside a cocoa tin and attached to a buoy made from a sheep’s bladder. This St Kilda mailboat was then thrown into the sea with instructions for anyone finding it to forward the mail. Believe it or not, over two thirds of mail sent in this way reached its destination. It is not uncommon for the Gulf Stream to carry them as far as the shores of Norway.

Yet another incredible tale from the islands, relates to an incident that occurred in the 1720s. Eight boys and three men from the main island of St Kilda were dropped off by boat on a remote sea stack named Stac an Armin to collect seabirds. A smallpox outbreak on the main island then prevented anyone from being able to man a boat and collect them. They survived for 9 months, including one whole winter, on this tiny rocky pinnacle without communication or supplies before they were rescued. Considering how many died from smallpox they were probably the lucky ones.

The sense of isolation and the difficulty in getting here must surely play a part in the attraction of the island, but visiting is however not nearly as fraught as it was when the islanders depended on open vessels making the perilous journey, often over a number of days and braving massive swells. In calm weather, high speed ribs can now make the journey from Miavaig harbour in Harris in a couple of hours. For paddle fans, the journey is one of the most sought after trips in the country. Only a handful of the most super fit and experienced sea kayakers manage it every year, which adds to the mystique of this challenging and demanding journey.

We believe that a trip to St Kilda is something everyone should do in their lifetime.