I have lived in Argyll, on and off, for almost all of my rather long life. Or at least in the lost lands of Argyll, the bit that was shuffled out of the local authority in the early 1970s.

My presence was far more off than on for almost four decades, so my bird observations were very seasonal. However, since the turn of the millennium it has been my permanent home. My family has been studying nature here for far longer. My father (John Raven) was mainly a botanist and gives a mention to the low mountains of Morvern and their exceptional alpine-arctic flora in his chapters in

Mountain Flowers (Raven & Walters, 1956). Earlier still, just after the war, he exposed a famous botanical fraud on the nearby Isle of Rum (see Sabbagh, 2016). He was an expert, in plants and butterflies. I am not. In fact, I am a poor birder, with very limited knowledge, and quite ignorant of certain bird species. But I do take a keen interest in everything I see. So it is possible that some of what I have noticed may interest a wider audience.

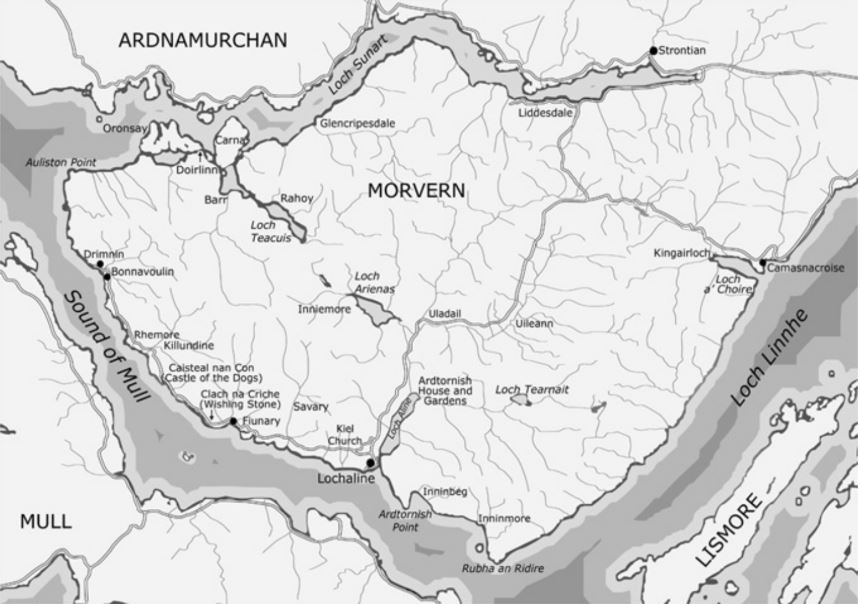

Many previous articles in the Eider have commented on species that have disappeared, and others that have newly arrived. So I might start there. Morvern is almost an island, and with our adjacent islets we have around 160km of coastline.

Probably the most significant change among seabirds has been the decimation of tern populations. During the 1970s I well remember the teeming colonies of Common Terns on islands in the Sound of Mull, and even on small rocky skerries offshore at Bonnavoulin. Those populations are long gone, as so graphically and sadly recorded by Clive Craik (Craik, 1997). We had Shelduck too. A pair was often to be seen at Fiunary. The couple I saw recently on Lismore was the first I have seen for probably 20 years. Eiders are also scarcer now than in the past. Red-breasted Mergansers were more abundant then, while Goosanders were an exciting rarity. That balance has now reversed. The Red-breasted Mergansers are still here, but in lower numbers than Goosanders, I counted nine drakes of the latter species in the outflow of the River Aline in mid-May this year. Both Greylag and Canada Geese are recent arrivals—the latter over the last 15 years, the former over perhaps the last 10 years.

Curlew numbers have dwindled dramatically. We still hear their wonderful fluting call, but see them now in ones, twos and threes, whereas formerly they arrived in flocks well into double figures. I fear that they may be the next iconic bird to go. Greenshank and Oystercatcher are here year-round while summer-visiting Common Sandpipers are still plentiful though less evident than before. Common Gulls are doing well, and they are often seen foraging (I assume for craneflies and other insects) on the pastures around Lochaline before returning to their breeding colony on a nearby hill loch. Black-throated divers appear to be just hanging on, while Red-throated appear to be faring better.

Morvern is known for its eagles; both species breed here still. White-tailed Eagles are seen far more frequently. We also have several pairs of the Golden Eagles, although they have poor long-term breeding success. Unreliable spring weather and a shortage of live prey at nesting time appear to be factors implicated in this low productivity.

Two White-tailed Eagle Chicks on the nest just prior to being ringed. © Alan Kennedy

On passerines I am particularly weak. This year I have seen more Bullfinches, but nary a sign of Greenfinches for many years. Chaffinches abound, Siskin bustle through the trees and Goldfinches seem more abundant than ever. One recent midwinter I saw a pair of Snow Bunting high on a nearby hill. Of the corvids, we have those you would expect. The Raven has increased greatly in number, but apparently not at the expense of Carrion and Hooded Crow. Around 15 years ago Jays arrived. I have seen just one Magpie, which I guess was blown here during a gale; similarly the occasional Rook, foraging through wrack piles on the foreshore. We may have Jackdaws, but I have not seen them here. Of Choughs we have none.

Rock Doves have recently arrived, their plumage largely without signs of Feral Pigeon introgression. When they leave their haunts in the down-pipe hoppers of Ardtornish House they are tempting prey for raptors. This spring, a badly ruffled Sparrowhawk, alive but stunned and festooned in shards of glass, was found inside what a moment before had been a large plate glass window. Wood pigeons cling on, but numbers seem never to wax or wane.

We believe Black Grouse have always been here, but now in perilously low numbers, though of my only three sightings in over 60 years, all have been in the last decade. Red Grouse are scarcely more common. Ptarmigan formerly resided on our highest hill—just shy of making a Corbett—but I’m now too lazy to go and see if they are still there. In May this year I could swear I heard the yaffle of a Green Woodpecker—most definitely a first. I hear daily the alarm call of its Great Spotted cousin—now far more abundant than I recall in former times. Twenty years ago I requested an illustrator, who was decorating bird motifs on the beams in our house, to include a Nuthatch. What a fool I felt when I realised they were not here. Fortunately, I can now stop blushing, for we know they now nest nearby.

I have little news of great or exciting bird rarities. I am too inexpert a birder to be considered a reliable witness. A Great Grey Shrike is almost all I can manage. Years ago, a happy day in the estate archives revealed a reference that puzzled me for months. “Roller with brass plate” was on the inventory at the 1929 death of Ardtornish’s previous owner. I assumed it was a device for printing, or possibly a meteorological instrument. The reality was clarified by an enquiry to the National Museum of Scotland (NMS). A “colourful bird of Mediterranean origin” was how it was described by its curator, having been shot on 10 September 1927 at Achaforse Wood on the Isle of Mull (Ritchie, 1930). The set specimen now resides in the NMS collection. My only observation of remotely comparable rarity is from an occasion in the 1970s when, with my father, I spotted a dull speckled brown bird crawling up a drystane dyke. Any dubiety about its identity was removed when it rotated its head through one hundred and eighty degrees to look at us.

Great Grey Shrike, 13 November 2013 © Alan Kennedy

With that, even I could not mistake a Wryneck. We still have Wood Warblers—though I have yet to hear one this season. Sedge, Willow and the occasional Grasshopper Warblers breed here, as well as Blackcaps and Chiffchaffs. I am told that Redstarts and Pied flycatchers frequent our woods in summer. Creating more of their habitat is among our main priorities. I manage Ardtornish—a block of land with almost 32km of coastline and some of Scotland’s better remnant oakwoods. These are now known as Atlantic Temperate Rainforests, and we have among the best remaining stands along the western seaboard. Indeed, acorns from the Gleann Geall woods at Ardtornish are the foundation for the resurgence of native oaks across this region. Apparently our oaks produce more reliable crops of acorns than any others known to the seed merchants, so they are gathered most years in their millions to produce seedlings for nurseries.

Nets under oak woodland to collect acorns © Hugh Raven

In practice, restoring and regenerating native woods often means reducing the impact of herbivores. For the five designated sites either partly or wholly on Ardtornish, the main negative impacts are invasive species and herbivore grazing. The former problem is being tackled by an RSPB-led Rhodedendron ponticum eradication scheme, initiated when the society in 2023 purchased from SNH the Glencripesdale Estate on the peninsula‘s north coast. We work with the local deer management group to address overgrazing. Fencing and accurate data on deer numbers obtained through drone counts are the main current tools; but in time we must move away from reliance on costly artificial barriers, and reduce sheep and deer impacts to levels that allow natural regeneration.

Apart from White-tailed Eagles, native species reintroduction has yet to reach the avian genera. Red squirrels were brought here by Trees for Life in 2020, and Native Oysters came a year or two later, and once again pave the Loch Aline seabed. Wood Ants have recently been translocated here from colonies facing obliteration in Ardnamurchan. Perhaps Beavers will be next? Though we are told our habitats are not yet suitable. Wild Cats just cling on here, but they too need habitat restoration for us to qualify for the release of captive bred companions.

I would like to think this peninsula, with nature reserves owned and managed both by the Scottish Wildlife Trust and the RSPB, might be among the most significant nature conservation zones in the west. Certainly the Scottish Wildlife Trust’s Rahoy Hills Reserve is noted for its exceptional biodiversity. Perhaps, a place for you to visit in the future?

Hugh Raven