Scotland has a rich and varied Halloween tradition. Over the years, traditional pagan rituals have largely been forgotten or adapted by the Christian church, into what we are familiar with today. But as this most mysterious of days approaches, there is no better time to have a closer look at what this day used to involve. Some traditions remain remarkably unchanged, some have evolved with the times and under the influence of the church, and some have faded completely from memory.

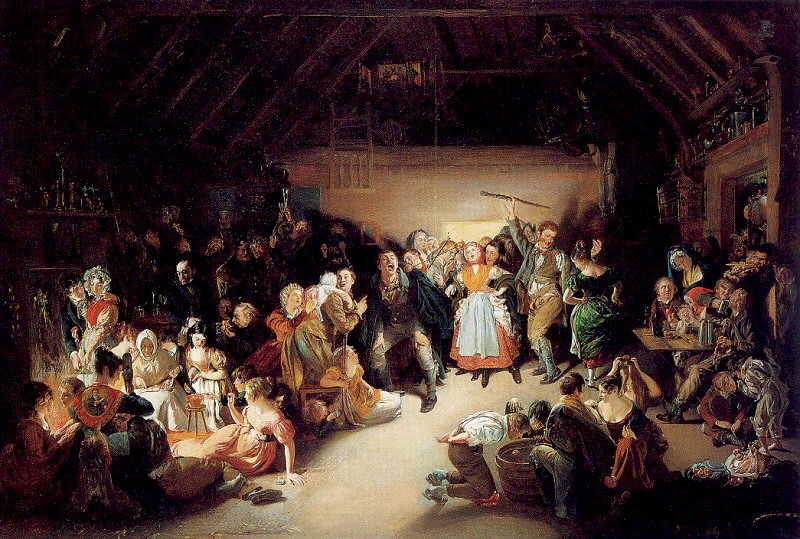

Samhain was a harvest festival; it marked the final harvest and the beginning of the onset of winter. It was an occasion for revelry as well as for making offerings to protect the cattle and crops over the coming winter. Held on the 31st October as this was regarded as a liminal time when the when the boundary between this world and the otherworld could more easily be crossed. To venture outside on this night was to risk being taken by the sluagh (the spirits of the restless dead). This explains the age-old custom of guising which we know today as trick or treating. The young men of the village would put on grotesque masks, or blacken their faces, before travelling out, to avoid being recognised and ‘taken’ by any of the spirits. The custom of going door-to-door collecting food for Samhain feasts, fuel for Samhain bonfires and offerings for the aos sí (fairies or nature spirits) would evolve into what we can easily recognise today. The night was also known as ‘mischief night’ due to the tradition of playing pranks, something that has been recorded as far back as the 1700’s.

Around the eighth century or so, the Catholic Church decided to use November 1st as All Saints Day. This was actually a shrewd manoeuvre, as pagans were already celebrating that day anyway, so it made sense to use it as a church holiday. All Saints became the festival to honour any saint who didn’t already have a day of his or her own. The mass which was said on this day was known as Allhallowmas – the mass of all those who are hallowed. The night before naturally became known as All Hallows Eve which over time changed into what we now call Halloween.

In the Hebrides, the bier on which a corpse is carried would be deliberately broken to prevent the sluagh using it to carry away the dead. The Cat Sith is a fairy creature from Celtic mythology that haunts the Highlands. On Samhain, it was believed that a Cat Sìth would bless any house that left a saucer of milk out for it to drink, and those houses that did not let out a saucer of milk would be cursed into having all their cows’ milk dry.

Communal sustenance was another common theme on this day and this can be seen in the custom of eating fuarag. This was a large dish of oatmeal and cream that was made in the Western Isles. The fuarag would be made in a large bowl (in some places using potatoes instead of cream), and into the bowl would be placed a ring, a coin and a button. All the boys and girls would sit around the table, supping with spoons, until all the objects had been found. Whoever got the ring would be the first to wed, the one who found the coin would see riches. Finding the button would mean you would never marry. Although as a custom this has all but died out in the islands it is heartening to know that it still lives on in Canada. In parts of Cape Breton, a region that still clings to its traditional roots eating fuarag on Halloween is as normal as trick or treating.

Fire would also play an important role in any Samhain ritual. Sometimes, two bonfires would be built side by side, and the people, sometimes with their cattle would walk between them as a cleansing ritual. The bones of slaughtered cattle would also have been cast upon bonfires. In parts of Scotland, torches of burning fir or turf were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them. In some places, people doused their hearth fires on Samhain night. Each family then solemnly re-lit its hearth from the communal bonfire, thus bonding the families of the village together.

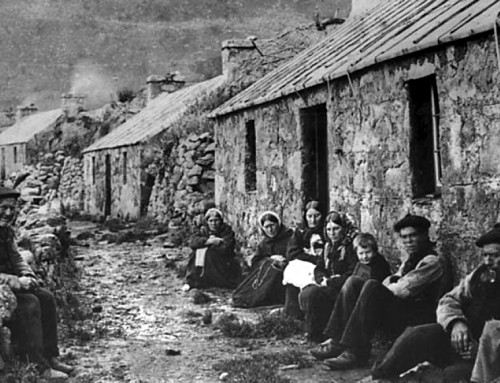

Celtic festival of Samhain

Pumpkin carving is a great example of the evolution of an ancient tradition. In Scotland a turnip would be hollowed out, a basic face made and a light put inside, a practice that many can still remember. Emigrants to the new world took their beliefs and traditions with them but found that pumpkins as well as being in abundance at this time of year actually made for easier carving due to their softer flesh. Rather than be disappointed at the historical inaccuracy of this adaptation of a culturally important ritual, I take the opposite view. It’s this very change that has popularised the custom and made it ubiquitous and this is the reason that our ancient beliefs will be preserved.

Halloween Pumpkins

A fascinating and ancient Samhain ritual, that sadly no longer takes place, is that of Christians on the Isle of Lewis who made offerings to the sea god, Shony, as late as the 17th century. The renowned folklorist Martin Martin writing in 1695 described the ceremony which took place at St Moluag’s church on the north of Lewis. The congregation would gather from afar, with every family contributing grain which was brewed into ale at the church. At night, they would walk down to Stoth bay where one man would take a cup of this ale and wade out into the sea up to his waist. As he poured the ale into the sea as an offering to Shony he would ask for plentiful supply of seaweed for the coming year. The party would then return to the church for a period of solemnity, then when a candle burning on the altar was blown out they went out into the fields, and drank the remaining ale while they danced and sung all night. The practice was eventually stopped by Presbyterian elements within the church, but the original building still stands. It was used as a cure for insanity right up until the 1890s. There have been efforts by the church to distance themselves from practices like this, to deny their very existence or portray accounts as fictional or fanciful. The similarities between this ritual and others recorded on the west coast of Ireland at roughly the same time would seem to indicate that fabrication is unlikely.

An equally bizarre Samhain ritual, but one that has incredibly survived to this day, revolves around the statues of An Cailleach in Glen Lyon in Perthshire. This is the oldest uninterrupted pagan ritual on record, so old in fact, nobody can say for sure just when it originated. Deep in the glen there is a small hut which houses a number of stones which represent the Cailleach, a creator deity in Celtic folklore. This site is recognised as the only surviving shrine to the ancient Celtic goddess and is one of the few examples of the continuity of ancient beliefs from the past to the present day. According to local lore, the Cailleach and her family were once given shelter in the glen by the local people. So grateful was she for the hospitality given to her family, that she left the stones with the promise that, as long as they were cared for, she would ensure the glen would continue to be fertile and prosperous. Every year on Samhain the stones are ritually placed inside the hut for the winter, to be brought out again for the summer at Beltane on May 1st.

Tigh nam Bodach

As you carve a pumpkin tonight or watch children collect sweeties while dressed as ghouls, remember that the ritual you are taking part in is indeed part of something ancient. It’s easy to criticise modern Halloween celebrations as commercial and comical, but I would disagree. It is by the evolution of tradition that it is able to survive. And as long as it survives, it gives us an important link to our pre-Christian past.