In a world where digital entertainment, fast food and exotic foreign holidays are the norm, what place is there for something as unreconstructed and old fashioned as the Highland Games?

In a curious contrast to the speed of change in the modern world, the games have in recent years thrived, quite simply because they have not adapted to suit contemporary mores. If anything, it’s the wider world that has been influenced by the spectacle and authenticity of our games, not the other way round.

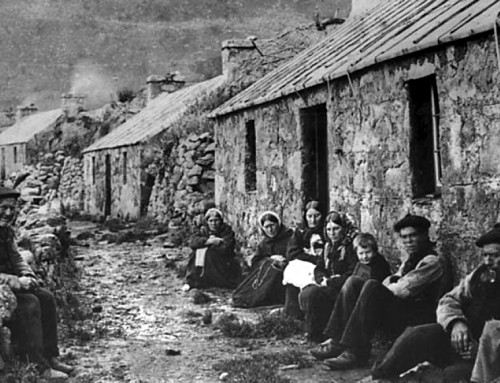

The exact origins of the games are unclear. Certainly there are apocryphal tales of ancient Scottish kings selecting the most able soldiers and couriers, by pitting young warriors against each other to find the fastest or strongest. Whatever format these tests of strength took, the break-up of the traditional clan system and the suppression of Highland culture in the aftermath of the battle of Culloden, meant that they very much took place in secret.

It was not until the Victorian era until the games as we know them now had a real resurgence. This was partially due to Queen Victoria herself, who was an avid spectator, and who started a long standing tradition of Royal patronage at the Braemar games, close to her residence at Balmoral. One of the joys of attending such a gathering today is that much of the spectacle seems relatively unchanged in the intervening years. The games are like a portal to a strange past, where tests of strength and musical ability take precedence over video games and football.

The exact composition of the days entertainments differs in local communities, but, as in the Victorian era, the highlights will always be the traditional dancing competitions, the massed pipes and drums and the so called heavy athletics. These include the caber, tug o’ war, hammer, shot putt and weight over a bar.

A curious legacy of this era is the connection with the modern Olympics. The founder of the International Olympic Committee, Baron Pierre de Coubertin attended the Paris Exhibition of 1889, where he saw a display of traditional Highland games and was so impressed that afterwards he introduced the hammer throw, shot put and tug o’ war to his then fledgling competition. It seems incredible now, but Olympic gold medals were indeed awarded to tug o’ war teams from 1900 to 1920. Stakes these days are considerably higher with local pride and bragging rights at stake.

Tossing the caber at the Oban highland games.

Hammer throwing as a competitive sport has evolved since its first Olympic inclusion, but its origins date as far back as the 13th and 14th century. King Edward I of England prohibited Scotsmen from being in possession of weapons in case they used them against the English during the Wars of Scottish Independence. Canny clansmen, looking to take part in military training, ended up doing so using tools as improvised weapons and the event was born. The hammer used in competition today still differs from its Olympic counterpart, in that it has a solid wooden shaft.

Oban high school pipe band at the Oban highland games.Argyll.

So what else could you expect to see at a highland games? Probably the most distinctive of the so called heavy events would be tossing the caber. Here, a larch tree up to 20 foot long is hurled end over end in a supreme test of technique, balance and brute strength. A spectator favourite, this unique event has, more than anything, come to symbolise Highland games the world over.

A traditional west coast favourite, enjoying a bit of a resurgence in popularity, is the Maide Leisg. Gaelic for Lazy Stick, this very simple test of strength is thought to originate in Carloway on Lewis and involves two men sitting on the ground with the soles of their feet pressing against each other. They then grab a stick between their hands and pull against each other until one of them is raised from the ground. Red Bull, more famous for their sponsorship of extreme sports, recently endorsed this most old fashioned activity with a nationwide competition that pitted teams of university rugby players against rowers and hockey players. Bandwagon jumping, or merely a recognition of one of the most fun participation sports out there?

In addition to athletics, Highland games also feature traditional dancing competitions and pipe band demonstrations. These make for an evocative spectacle, a stirring centerpiece for any gathering and more than anything else they illustrate how a shared history can bring people together.

It’s not just about showing off who is strongest, fittest or best-rehearsed it’s about the keeping alive of a tradition, a culture and a community spirit. The Scottish diaspora, in particular after the Highland Clearances, needed a way of connecting with the old country, of preserving a heritage and history a world away and they found that in Highland gatherings. Over 50,000 spectators attended the games in San Francisco in 2015, it is an institution then, that is in very good health. It is self-sustaining because it does not pander to the modern world – a day out in California can still closely resemble one in Scotland, a hundred years ago and 5 thousand miles away.

On a more local level the games are a time for family and reunions. In the rural parts of the Highlands and Islands, young folk who have left their communities for work or marriage, time their return home in the summer to coincide with the games. It’s a focal point for catching up with old friends, having a ceilidh and remembering the past. If you are lucky enough to attend a games this summer, bear in mind that what you are taking part in is not just a tourist show, it’s a time capsule of a long gone Scotland.

We think Morvern Highland Games held on Saturday 14 July 2018 are “the most scenic Highland Games in Scotland” they are followed by a week-long program of events offering fun for all the family.

Photo credits Dennis Hardley Photography Oban

(except Highland Dancer which was via CC)